I was recently delighted to be interviewed by Adam Hawkins on his podcast Small Batches. We discussed a huge variety of topics. Here is the full episode, and on that page you’ll find meticulously timestamped links to specific topics. Check out the rest of Adam’s podcast, it’s phenomenal!

Tag: medical reasoning

No Observability Without Theory: The Talk

Last month, I had the unadulterated pleasure of presenting “No Observability Without Theory” at Monitorama 2024. If you’ve never been to Monitorama, I can’t recommend it enough. I think it’s the best tech conference, period.

This talk was adapted from an old blog post of mine, but it was a blast turning it into a talk. I got to make up a bunch of nonsense medical jargon, which is one of my favorite things to do. Here are my slides, and the video is below. Enjoy!

Explaining the fire

When your site goes down, it’s all hands on deck. A cross-functional team must assemble fast and pursue an organized response. It feels like fighting a fire. So it’s not surprising that formal IT incident management tends to borrow heavily from the discipline of firefighting.

However, in software incident response, we have a crucial constraint that you won’t find in firefighting. Namely, in order to fix a software product, we first have to understand why it’s broken.

When the firefighters arrive at the blazing building, they don’t need to explain the fire. They need to put it out. It doesn’t matter whether a toaster malfunctioned, or a cat knocked over a candle, or a smoker fell asleep watching The Voice. The immediate job is the same: get people to safety and put out the fire.

But when PagerDuty blows up and we all stumble into the incident call, we need at least a vague hypothesis. Without one, we can’t even start fixing the problem. What should we do? Reboot one of the web servers? Which one? Should we revert the last deploy? Should we scale up the database? Flush the CDN? Open a support ticket with Azure? Just wait?

We can’t act until we have at least some explanation for how the outage came about.

Often, the process of diagnosis – of explaining the failure – takes up the majority of the incident. Diagnosis isn’t easy, especially in a group and under pressure. Important facts go ignored. Hypotheses get forgotten, or remain unchallenged in the face of new information. Action items fall through the cracks. Diagnostic disconnects like these add up to longer outages, noisier public-facing comms, and repeat failures.

And yet, when we look to improve IT incident response, what do we usually focus on? On-call rotations, status page updates, command-and-control structure. Sliding-down-the-firepole, radioing-with-dispatch type stuff.

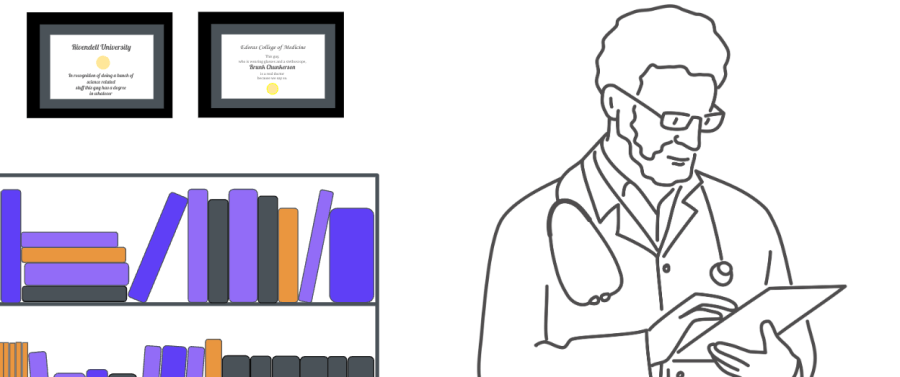

In software incident response, we need to maintain a coherent diagnostic strategy in the face of scarce information and severe time pressure. This makes us, on one dimension at least, more like doctors than firefighters. This is one of the reasons that engineering teams find immense value in clinical troubleshooting. It brings rigor and transparency to the joint diagnostic effort.

I teach clinical troubleshooting as part of Scientific Incident Response in 4 Days. Check it out.

I was on the Slight Reliability podcast!

Thanks very much to host Stephen Townshend of Slight Reliability podcast. We talked about incident response, diagnosis, and looking for trouble. It was very chill!

Full 28-minute episode:

Clinical troubleshooting: diagnose any production issue, fast.

Over my career as an SRE, I’ve diagnosed thousands of production issues. When I’m lucky, I have enough information at hand, and enough expertise in the systems involved, to get to the bottom of the problem on my own. But very often I need to bring together a team.

Troubleshooting with a team unleashes enormous power. Problems that would have taken me days to solve as an individual might take only hours or minutes, thanks to the benefit of pooled knowledge.

However, collaborative troubleshooting also comes with dangers. Time and again, I’ve seen groups struggle to make progress on an investigation due to miscommunication, misalignment, and confusion. Among other difficulties, the fundamental common ground breakdown can have especially heinous consequences in this context.

Over the years, I’ve developed a reliable method for harnessing the diagnostic power of groups. My approach is derived from a different field in which groups of experts with various levels of context need to reason together about problems in a complex, dynamic system: medicine.

I call this method clinical troubleshooting.

The clinical troubleshooting process

Although clinical troubleshooting can be useful in solo troubleshooting, it really shines as a group activity. It’s a lightweight structure that always adds value. I recommend reaching for clinical troubleshooting as soon as you need to involve another person in any “why” question about an unexpected behavior of your system.

Step 0: Get a group together

Before you start, gather the people you’ll be troubleshooting with. Any synchronous communication channel can work for this: Slack, Zoom, a meeting room; you name it.

You don’t need a big group. In fact, a small group is best. What matters most is that you bring together diverse perspectives. If you’re a backend engineer, try to pull in a network engineer and a frontend engineer, or a support agent and a sysadmin. Cast a wide net.

Once you have an initial group, share a blank Google doc with everyone.

Step 1: Identify symptoms

Add a Symptoms header to the doc.

You’re the one bringing the issue, so you must have some observations already. Write those down in a numbered list.

It’s important that it be a numbered list rather than a bulleted list. As the troubleshooting process goes on, you’re going to want to refer to individual symptoms (and, later, hypotheses and actions). If each symptom has a number and the number never changes, this is a lot easier.

Ask your collaborators to list symptoms, too. They may have observed some other facet of the problem, or they may think to look at a graph that you don’t know about.

Here’s what an initial symptom list might look like:

Symptoms

- About 5 times a day, the Storage API sends a spike of 503 responses. Each spike lasts about 500 milliseconds and includes between 200 and 1000 responses (about 0.1 to 0.5% of all responses sent during the interval)

- Outside of these spikes, the Storage API has not sent any 503 responses at all in the last 14 days.

- The failing requests have short durations, around the same as those of normal requests (mostly under 100 milliseconds).

(In this and subsequent examples, don’t worry about understanding the exact technical situation. Clinical troubleshooting can be used on problems in any part of any tech stack.)

All the symptoms on the list should be precise and objective. In other words, if a statement is quantifiable, quantify it. Don’t make suppositions yet about why these phenomena have been observed. That comes next.

Once you’re all on the same page about what problem you’re investigating, the initial symptom list is done.

Step 2: Brainstorm hypotheses

Add a Hypotheses header to the doc. Invite your colleagues to join you in suggesting hypotheses that might explain the symptoms.

Let the ideas flow, and write them all down. This is where having a diverse set of perspectives in the room really pays off. Your co-investigators will think of hypotheses that would never have occurred to you, and vice versa. The more of these you come up with, the more likely the actual explanation will be on the list.

A hypothesis can’t be just anything, though. A hypothesis must

- explain (at least some of) the symptoms,

- accord with all known facts, and

- be falsifiable (that is: if it were false, we’d be able somehow to prove it false).

For example, given the symptoms above, “requests to the storage API are getting queued up behind a long-running query” would not be a sound hypothesis, since it’s inconsistent with Symptom 3. If requests were queued up, we’d expect them to take longer before failing.

After some discussion, your hypothesis list might look like this:

Hypotheses

- A particular request causes an out-of-memory (OOM) event on a storage server, and all in-flight requests to that server get killed.

- A network hiccup causes connections between the load balancer and a storage server to be severed.

Requests to the storage API are getting queued up behind a long-running queryDiscarded because inconsistent with Symptom 3

- A network hiccup causes connections between storage API servers and a persistence layer node to be severed.

Again, use a numbered list. If a hypothesis is ruled out or deemed irrelevant, don’t delete it: you don’t want the list numbering to change. Instead, mark it in some with formatting. I use strikethrough. Gray works too.

Step 3: Select actions

Add an Actions header.

In a new numbered list, choose one or two actions that will advance the troubleshooting effort. Usually, you should pick actions that will rule out, or “falsify,” one or more of the hypotheses on the table.

To rule out Hypothesis 2 above, for instance, you could review the logs for one of the error spikes and check whether all the affected requests were associated with the same load balancer or the same storage server. If the requests are distributed across your infrastructure, then Hypothesis 2 is ruled out (and Hypothesis 1 as well, for that matter!).

When you agree upon actions, it’s best to assign them to individuals. Sometimes an action can be taken right away, and other times it’ll take a while and the group will have to reconvene later. But ownership should never be unclear.

Ruling out hypotheses the only purpose of actions in clinical troubleshooting. You can also assign actions that expand the group’s understanding of the problem, in order to generate new symptoms and new hypotheses. These actions can be things like, “Read the documentation on system X‘s network configuration,” or “Search for blog posts about error message E.” As long as there’s at least one hypothesis in the running, though, there ought to be at least one action in flight that could falsify it. That’s one of the ways clinical troubleshooting ensures constant progress.

Steps 4 through N: Cycle back through

When actions are completed, you get more information for the symptom list. More symptoms suggest new hypotheses. New hypotheses imply further actions. Just keep going through the cycle until you’re satisfied.

Sometimes you won’t be satisfied until you have a definitive diagnosis: a solid explanation for all the symptoms that’s been proven right. Other times, you’ll be satisfied as soon as you take an action that makes the problem go away, even if there’s still uncertainty about what exactly was going on.

In any case, clinical troubleshooting will reliably get you to the solution.

Keep things moving forward

In the absence of structure, collaborative diagnosis can stall out. Or worse, go backward.

With clinical troubleshooting, there’s always a next step forward. Teams that practice this method will consistently get to the bottom of technical mysteries, even when strapped for data or under intense pressure. And over time, as this scientific way of thinking becomes a habit, and then a culture, we come to understand the behavior of our system that much better.

I can teach your team how to do this. Get in touch.

3 questions that will make you a phenomenal rubber duck

As a Postgres reliability consultant and SRE, I’ve spent many hours being a rubber duck. Now I outperform even the incisive bath toy.

“Rubber duck debugging” is a widespread, tongue-in-cheek term for the practice of explaining, out-loud, a difficult problem that you’re stumped on. Often, just by putting our troubles into words, we suddenly discover insights that unlock progress. The person we’re speaking to could just as well be an inanimate object, like a rubber duck. Hence the term.

Rubber ducks are great, but a human can add even more value. In this article, I’ll share my 3 favorite questions to ask when someone comes to me feeling stumped in a troubleshooting endeavor. These questions work even when you have no particular expertise in the problem domain. Master them, and you’ll quickly start gaining a reputation as the person to talk to when you’re stuck. This is a great reputation to have!

Question 1: How did you first start investigating this?

As we investigate a problem, our focus shifts from one thing to another to another. We go down one path and forget about others. We zoom in on details and neglect to zoom back out. It’s easy to lose perspective.

“How did you first start investigating this?” works well because, through the act of recounting their journey from initial observation to where they are now, your colleague will often regain perspective they’ve lost along the way. And by asking this particular question, you avoid having to suggest that they may have lost perspective – which could make them defensive.

Even if your colleague hasn’t lost perspective, hearing the story of the investigation so far will help you ask better questions and help them organize their thoughts.

Question 2: What observations have you made?

In troubleshooting a complex problem, it’s easy to forget what you already know. As you go along, you make lots of observations, small and large, interesting and boring, relevant and irrelevant. You can’t hold them all in your head.

When someone’s stuck, it often helps to review their observations. Not theories, not difficulties, not actions: directly observed facts.

Reviewing observations can help in a few different ways:

- They may be entertaining a hypothesis that clashes with some previously learned (but since forgotten) fact. If so, they can now go ahead and discard that hypothesis.

- Juxtaposing two observations may suggest a hypothesis that never occurred to them before, because they never held those two observations in their head simultaneously.

- Listing out their observations may bring to mind something they haven’t looked at yet.

As your colleague recounts their observations, write them down in a numbered list. And, if you can, ask clarifying questions. Questions like “Does X always happen concurrently with Y, or only sometimes?” and “How does this differ from the normal behavior?”

Never underestimate the power of precisely stating the facts.

Question 3: If your hypothesis were wrong, how could we disprove it?

This question is my favorite.

One of the most common ways people get stuck in troubleshooting is tunnel vision. They get a single idea in their head about the cause of the problem, and that becomes all they can think about.

This question, “If your hypothesis were wrong, how could we disprove it?” flips the script. Instead of racking their brain trying to prove their theory, it gets them thinking about other possibilities. Asking this question can lead to lots of different outcomes, all of which represent progress:

- You come up with a way to disprove the hypothesis, and successfully disprove it. This may make your colleague sad for a few hours, but when they come back to the problem, they’ll make huge strides.

- You come up with a way to disprove the hypothesis, but fail to disprove it. The hypothesis is thus bolstered, and the next step becomes clear: elaborate a few different versions of it and try to disprove those.

- You can’t think of any way to disprove it. This means it’s probably not a hypothesis at all, since it’s not falsifiable. Therefore you must replace it with a new hypothesis. This may feel like a setback, but it’s really the only way forward.

How it fits together

Under the hood, these 3 questions are just different ways of invoking hypothetico-deductive reasoning, which I’ve written about previously (see Troubleshooting On A Distributed Team Without Losing Common Ground and You Know Who’s Smart? Friggin’ Doctors, Man.). I don’t know of any better way to achieve consistent problem-solving results in the face of complexity.

If you’re interested in learning how to apply these techniques in your career or in your organization, I can help. Shoot me an email!

Troubleshooting On A Distributed Team Without Losing Common Ground

I work on a team that fixes complex systems under time pressure. My teammates have different skill sets, different priorities, and different levels of expertise. But we all have to troubleshoot and solve problems together.

This is really hard to do effectively. Fortunately for us in the relatively new domain of DevOps, situations like ours have been studied extensively in the last couple decades. We can use the results of this research to inform our own processes and automation for troubleshooting.

One of the most important concepts to emerge from recent teamwork research, common ground, helps us understand why collaborative troubleshooting breaks down over time. This breakdown leads to wasted effort and mistakes, even if the team maintains constant communication in a chat room. But if we extend ChatOps by drawing on some ideas from medical diagnosis, we can make troubleshooting way easier without losing the benefits of fluid team conversation.

Common Ground

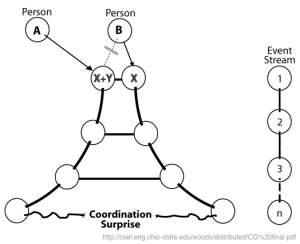

Ergonomics researchers D.D. Woods and Gary Klein (the latter of whom I wrote about in What makes an expert an expert?) published a phenomenally insightful paper in 2004 called Common Ground and Coordination in Joint Activity. In it, they describe a particular kind of failure that occurs when people engage in joint cognition: the Fundamental Common Ground Breakdown. Once you learn about the Fundamental Common Ground Breakdown, you see it everywhere. Here’s how the Woods/Klein paper describes the FCGB:

- Party A believes that Party B possesses some knowledge

- Party B doesn’t have this knowledge, and doesn’t know he is supposed to have it.

- Therefore, he or she doesn’t request it.

- This lack of a request confirms to Party A that Party B has the knowledge.

When this happens, Party A and Party B lose common ground, which Woods & Klein define as “pertinent knowledge, beliefs and assumptions that are shared among the involved parties.” The two parties start making incorrect assumptions about each other’s knowledge and beliefs, which causes their common ground to break down further and further. Eventually they reach a coordination surprise, which forces them to re-synchronize their understanding of the coordinated activity:

Seriously, the FCGB is everywhere. Check out the paper.

I’m especially interested in one particular area where an understanding of common ground can help us do better teamwork: joint troubleshooting.

Common Ground Breakdown in Chatroom Troubleshooting

Everybody’s into ChatOps these days, and I totally get it. When a critical system is broken, it’s super useful to get everybody in the same room and hash it out. ChatOps allows everybody to track progress, coordinate activities, and share results. And it also helps to have lots of different roles represented in the room:

- Operations folks, to provide insight into the differences between the system’s normal behavior and its current state

- Software engineers, who bring detailed knowledge of the ways subsystems are supposed to work

- Account managers and product managers and support reps: not just for their ability to translate technical jargon into the customer’s language for status reporting, but also because their understanding of customer needs can help establish the right priorities

- Q.A. engineers, who can rule out certain paths of investigation early with their intuition for the ways in which subsystems tend to fail

The process of communicating across role boundaries isn’t just overhead: it helps us refine our own understanding, look for extra evidence, and empathize with each other’s perspectives.

But ChatOps still offers a lot of opportunities for common ground breakdown. The FCGB can occur whenever different people interpret the same facts in different ways. Interpretations can differ for many different reasons:

- Some people have less technical fluency in the system than others. A statement like “OOM killer just killed Cassandra on db014” might change an ops engineer’s whole understanding of the problem, but such a shift could fly under the radar of, say, a support engineer.

- Some people are multitasking. They may have a stake in the troubleshooting effort but be unable to internalize every detail from the chat room in real time.

- Some people are co-located. They find it easier to discuss the problem using mouth words or by physically showing each other graphs, thereby adjusting their own shared understanding without transmitting these adjustments to the rest of the team.

- Some people enter the conversation late, or leave for a while and come back. These people will miss common ground changes that happen during their absence.

These FCGB opportunities all become more pronounced as the troubleshooting drags on and folks become tired, bored, and confused. And when somebody says they’ve lost track of common ground, what do we do? Two main things: we provide a summary of recent events and let the person ask questions until they feel comfortable; or we tell them to read the backlog.

The Q&A approach has serious drawbacks. First of all, it requires somebody knowledgeable to stop what they’re doing and summarize the situation. If people are frequently leaving and entering the chat room, you end up with a big distraction. Second of all, it leaves lots of room for important information to get missed. The Fundamental Common Ground Breakdown happens when somebody doesn’t know what to ask, so fixing it with a Q&A session is kind of silly.

The other way people catch up with the troubleshooting effort is by reading the backlog. This is even more inefficient than Q&A. Here’s the kind of stuff you have to dig through when you’re reading a chat backlog:

There’s a lot to unpack there – and that’s just 18 messages! Imagine piecing together a troubleshooting effort that’s gone on for hours, or days. It would take forever, and you’d still make a lot of mistakes. It’s just not a good way to preserve common ground.

So what do we need?

Differential Diagnosis as an Engine of Common Ground

I’ve blogged before about how much I love differential diagnosis. It’s a formalism that doctors use to keep the diagnostic process moving in the right direction. I’ve used it many times in ops since I learned about it. It’s incredibly useful.

In differential diagnosis, you get together with your team in front of a whiteboard – making sure to bring together people from a wide variety of roles – and you go through a cycle of 3 steps:

- Identify symptoms. Write down all the anomalies you’ve seen. Don’t try to connect the dots just yet; just write down your observations.

- Generate hypotheses. Brainstorm explanations for the symptoms you’ve observed. This is where it really helps to have a good cross-section of roles represented. The more diverse the ideas you write down, the better.

- Test hypotheses. Now that you have a list of things that might be causing the problem, you start narrowing down that list by coming up with a test that will prove or disprove a certain hypothesis.

Once you’re done with step #3, you can cross out a hypothesis or two. Then you head back to step #1 and repeat the cycle until the problem is identified.

A big part of the power of differential diagnosis is that it’s written down. Anybody can walk into the room, read the whiteboard, and understand the state of the collaborative effort. It cuts down on redundant Q&A, because the most salient information is summarized on the board. It eliminates inefficient chat log reading – the chat log is still there, but you use it to search for specific pieces of information instead of reading it like a novel. But, most importantly, differential diagnosis cuts down on fundamental common ground breakdowns, because everybody has agreed to accept what’s on the whiteboard as the canonical state of troubleshooting.

Integrating Differential Diagnosis with ChatOps

We don’t want to lose the off-the-cuff, conversational nature of ChatOps. But we need a structured source of truth to provide a point-in-time understanding of the effort. And we (read: I) don’t want to write a whole damn software project to make that happen.

My proposal is this: use Trello for differential diagnosis, and integrate it with the chat through a Hubot plugin. I haven’t written this plugin yet, but it shouldn’t take long (I’ll probably fork hubot-trello and start from there). That way people could update the list of symptoms, hypotheses, and tests on the fly, and they’d always have a central source of common ground to refer to.

In the system I envision, the chat room conversation would be peppered with statements like:

Geordi: hubot symptom warp engine going full speed, but ship not moving

Hubot: Created (symp0): warp engine going full speed, but ship not moving

Beverly: hubot falsify hypo1

Hubot: Falsified (hypo1): feedback loop between graviton emitter and graviton roaster

Geordi: hubot finish test1

Hubot: Marked (test1) finished: reboot the quantum phase allometer

And the resulting differential diagnosis board, containing the agreed-upon state of the troubleshooting effort, might look like this example, with cards labeled to indicate that they’re no longer in play.

What do you think?

Let me know if your organization already has something like this, or has tried a formal differential diagnosis approach before. I’d love to read some observations about your team’s process in the comments. Also, VictorOps has a pretty neat suite of tools that approaches what I have in mind, but I still think a more conceptually structured (not to mention free) solution could be very useful.

Automation is most effective when it’s a team player. By using automation to preserve common ground, we can solve problems faster and more thoroughly, with less frustration and less waste. And that all sounds pretty good to me.

You Know Who’s Smart? Friggin’ Doctors, Man.

Inspired by Steve Bennett‘s talk at Velocity 2012 (slides here. I swear it’s a great talk; I didn’t just think he was smart because he’s British), I’ve been trying lately to apply medicine’s differential diagnosis approach to my ops problem solving.

If you’ve ever seen an episode of “House M.D,” you’ll recognize the approach right away.

Problem-Based Learning

Since my girlfriend (partner/common-law fiancée/non-Platonic ladyperson/whatever) is a veterinary student, I end up hearing a lot about medical reasoning. One of her classes in first year was “Problem-Based Learning,” or as I called it, “House D.V.M.”. The format of this class should sound familiar to anyone who’s worked in ops, or dev, or the middle bit of any Venn diagram thereof.

You walk in on Monday and grab a worksheet. This worksheet describes the symptoms of some cat or pug or gila monster or headcrab that was recently treated in the hospital. Your homework: figure out what might be wrong with the animal, and recommend a course of treatment and testing.

On Tuesday, you’re given worksheet number 2. It says what a real vet did, given Monday’s info, and then it lists the results of the tests that the vet ordered. So the process starts over: your homework is to infer from the test results what could be wrong with the animal, and then figure out what tests or treatments to administer next.

This process repeats until Friday, by which point you’ve hopefully figured out what the hell.

When I heard this, I thought it was all very cool. But I didn’t pick up on the parallels with my own work, which are staggering. And what really should have caught my attention, in retrospect, is that this was a course they were taking. They’re teaching a deductive process!

Can We Formalize It? Yes We Can!

In tech, our egos often impede learning. We’re smart and we’ve built a unique, intricate system that nobody else understands as well as we do. “Procedures” and “methodologies” disgust us: it’s just so enterprisey to imagine that any one framework could be applied to the novel, cutting-edge complexities we’re grokking with our enormous hacker brains.

Give it a rest. Humans have been teaching each other how to troubleshoot esoteric problems in complex systems for friggin millennia. That’s what medicine is.

When faced with a challenging issue to troubleshoot, doctors will turn to a deductive process called “differential diagnosis.” I’m not going to describe it in that much detail; if you want more, then tell Steve Bennett to write a book. Or watch a few episodes of House. But basically the process goes like this:

- Write down what you know: the symptoms.

- Brainstorm possible causes (“differentials”) for these symptoms.

- Figure out a test that will rule out (“falsify”) some of the differentials, and perform the test.

- If you end up falsifying all your differentials, then clearly you didn’t brainstorm hard enough. Revisit your assumptions and come up with more ideas.

This simple process keeps you moving forward without getting lost in your own creativity.

Mnemonics As Brainstorming Aids

The brainstorming step of this deductive process (“writing down your differentials”) is critical. Write down whatever leaps to mind.

Doctors have mnemonic devices to help cover all the bases here. One of the most popular is VINDICATE (Vascular/Inflammatory/Neoplastic/Degenerative/Idiopathic/Congenital/Autoimmune/ Traumatic/Endocrine). They go through this list and ask “Could it be something in this category?” The list covers all the systems in the body, so if the doctor seriously considers each of the letters, they’ll usually come up with the right differential (although they may not know it yet).

Vets have a slightly different go-to mnemonic when listing differentials: DAMNIT. There are several different meanings for each letter, but the gist of it is Degenerative, Anomalous, Metabolic, Nutritional, Inflammatory, Traumatic. Besides being a mild oath (my second-favorite kind of oath), this device has the advantage of putting more focus on the trouble’s mode of operation, rather than its location.

These mnemonics are super useful to doctors, and it’s not that hard to come up with your own version. Bennett suggests CASHWOUND (see his slides to find out why).

No Seriously, Try It. It’s Great.

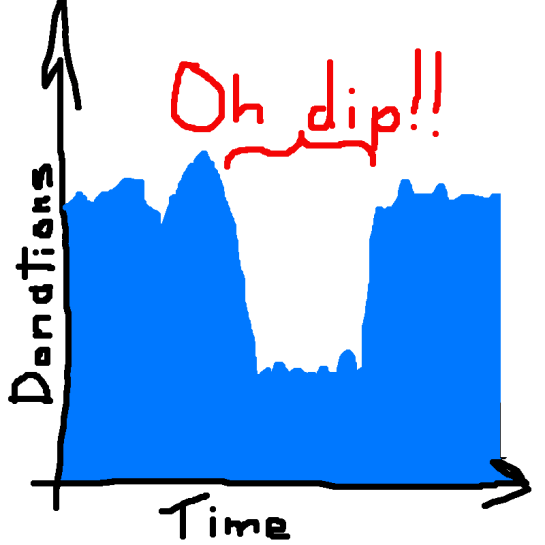

The other day, we were looking at our contribution dashboard and we noticed this (artist’s rendering):

That dip in donations lasted about 10 minutes, and we found it extremely disturbing. So we piled into a conference room with a clean whiteboard, and we started writing down differentials.

A. Firewall glitch between card processors and Internet

B. Database failure causing donation pages not to load

C. Failures from the third-party payment gateway

D. Long response times from the payment gateway

E. Errors in our payment-processing application

F. DNS lookup failures for the payment gateway

Admittedly this is not a very long list, and we could’ve brainstormed better. But anyway, we started trying to pick apart the hypotheses.

We began with a prognostic approach. That means we judged hypothesis (B) to be the most terrifying, so we investigated it first. We checked out the web access logs and found that donation pages had been loading just fine for our users. Phew.

The next hypotheses to test were (C) and (D). Here we had switched to a probabilistic approach — we’d seen this payment gateway fail before, so why shouldn’t it happen again? To test this hypothesis, we checked two sources: our own application’s logs (which would report gateway failures), and Twitter search. Neither turned up anything promising. So now we had these differentials (including a new one devised by my boss, who had wandered in):

A. Firewall glitch between card processors and Internet

B. Database failure causing donation pages not to load

C. Failures from the third-party payment gateway

D. Long response times from the payment gateway

E. Errors in our payment-processing application

F. DNS lookup failures for the payment gateway

G. Users were redirected to a different site

(E) is pretty severe (if not particularly likely, since we hadn’t deployed the payment-processing code recently), so we investigated that next. No joy — the application’s logs were clean. Next up was (A), but it proved false as well, since we found no errors or abnormal behavior in the firewall logs.

So all we had left was (F) and (G). Finally we were able to determine that a client was A/B testing the donation page by randomly redirecting half of the traffic with Javascript. So everything was fine.

Throughout this process, I found that the differential diagnosis technique helped focus the team. Nobody stepped on each other’s toes, we were constantly making progress, and nobody had the feeling of groping in the dark that one can get when one troubleshoots without a method.

Try it out some time!