I was recently delighted to be interviewed by Adam Hawkins on his podcast Small Batches. We discussed a huge variety of topics. Here is the full episode, and on that page you’ll find meticulously timestamped links to specific topics. Check out the rest of Adam’s podcast, it’s phenomenal!

Tag: differential diagnosis

No Observability Without Theory: The Talk

Last month, I had the unadulterated pleasure of presenting “No Observability Without Theory” at Monitorama 2024. If you’ve never been to Monitorama, I can’t recommend it enough. I think it’s the best tech conference, period.

This talk was adapted from an old blog post of mine, but it was a blast turning it into a talk. I got to make up a bunch of nonsense medical jargon, which is one of my favorite things to do. Here are my slides, and the video is below. Enjoy!

Podcast appearance: The Debrief from Incident.io

I’m so grateful to Incident.io for the opportunity to shout from their rooftop about Clinical troubleshooting, which I firmly believe is the way we should all be diagnosing system failures. Enjoy the full episode!

Explaining the fire

When your site goes down, it’s all hands on deck. A cross-functional team must assemble fast and pursue an organized response. It feels like fighting a fire. So it’s not surprising that formal IT incident management tends to borrow heavily from the discipline of firefighting.

However, in software incident response, we have a crucial constraint that you won’t find in firefighting. Namely, in order to fix a software product, we first have to understand why it’s broken.

When the firefighters arrive at the blazing building, they don’t need to explain the fire. They need to put it out. It doesn’t matter whether a toaster malfunctioned, or a cat knocked over a candle, or a smoker fell asleep watching The Voice. The immediate job is the same: get people to safety and put out the fire.

But when PagerDuty blows up and we all stumble into the incident call, we need at least a vague hypothesis. Without one, we can’t even start fixing the problem. What should we do? Reboot one of the web servers? Which one? Should we revert the last deploy? Should we scale up the database? Flush the CDN? Open a support ticket with Azure? Just wait?

We can’t act until we have at least some explanation for how the outage came about.

Often, the process of diagnosis – of explaining the failure – takes up the majority of the incident. Diagnosis isn’t easy, especially in a group and under pressure. Important facts go ignored. Hypotheses get forgotten, or remain unchallenged in the face of new information. Action items fall through the cracks. Diagnostic disconnects like these add up to longer outages, noisier public-facing comms, and repeat failures.

And yet, when we look to improve IT incident response, what do we usually focus on? On-call rotations, status page updates, command-and-control structure. Sliding-down-the-firepole, radioing-with-dispatch type stuff.

In software incident response, we need to maintain a coherent diagnostic strategy in the face of scarce information and severe time pressure. This makes us, on one dimension at least, more like doctors than firefighters. This is one of the reasons that engineering teams find immense value in clinical troubleshooting. It brings rigor and transparency to the joint diagnostic effort.

I teach clinical troubleshooting as part of Scientific Incident Response in 4 Days. Check it out.

I was on the Slight Reliability podcast!

Thanks very much to host Stephen Townshend of Slight Reliability podcast. We talked about incident response, diagnosis, and looking for trouble. It was very chill!

Full 28-minute episode:

Clinical troubleshooting: diagnose any production issue, fast.

Over my career as an SRE, I’ve diagnosed thousands of production issues. When I’m lucky, I have enough information at hand, and enough expertise in the systems involved, to get to the bottom of the problem on my own. But very often I need to bring together a team.

Troubleshooting with a team unleashes enormous power. Problems that would have taken me days to solve as an individual might take only hours or minutes, thanks to the benefit of pooled knowledge.

However, collaborative troubleshooting also comes with dangers. Time and again, I’ve seen groups struggle to make progress on an investigation due to miscommunication, misalignment, and confusion. Among other difficulties, the fundamental common ground breakdown can have especially heinous consequences in this context.

Over the years, I’ve developed a reliable method for harnessing the diagnostic power of groups. My approach is derived from a different field in which groups of experts with various levels of context need to reason together about problems in a complex, dynamic system: medicine.

I call this method clinical troubleshooting.

The clinical troubleshooting process

Although clinical troubleshooting can be useful in solo troubleshooting, it really shines as a group activity. It’s a lightweight structure that always adds value. I recommend reaching for clinical troubleshooting as soon as you need to involve another person in any “why” question about an unexpected behavior of your system.

Step 0: Get a group together

Before you start, gather the people you’ll be troubleshooting with. Any synchronous communication channel can work for this: Slack, Zoom, a meeting room; you name it.

You don’t need a big group. In fact, a small group is best. What matters most is that you bring together diverse perspectives. If you’re a backend engineer, try to pull in a network engineer and a frontend engineer, or a support agent and a sysadmin. Cast a wide net.

Once you have an initial group, share a blank Google doc with everyone.

Step 1: Identify symptoms

Add a Symptoms header to the doc.

You’re the one bringing the issue, so you must have some observations already. Write those down in a numbered list.

It’s important that it be a numbered list rather than a bulleted list. As the troubleshooting process goes on, you’re going to want to refer to individual symptoms (and, later, hypotheses and actions). If each symptom has a number and the number never changes, this is a lot easier.

Ask your collaborators to list symptoms, too. They may have observed some other facet of the problem, or they may think to look at a graph that you don’t know about.

Here’s what an initial symptom list might look like:

Symptoms

- About 5 times a day, the Storage API sends a spike of 503 responses. Each spike lasts about 500 milliseconds and includes between 200 and 1000 responses (about 0.1 to 0.5% of all responses sent during the interval)

- Outside of these spikes, the Storage API has not sent any 503 responses at all in the last 14 days.

- The failing requests have short durations, around the same as those of normal requests (mostly under 100 milliseconds).

(In this and subsequent examples, don’t worry about understanding the exact technical situation. Clinical troubleshooting can be used on problems in any part of any tech stack.)

All the symptoms on the list should be precise and objective. In other words, if a statement is quantifiable, quantify it. Don’t make suppositions yet about why these phenomena have been observed. That comes next.

Once you’re all on the same page about what problem you’re investigating, the initial symptom list is done.

Step 2: Brainstorm hypotheses

Add a Hypotheses header to the doc. Invite your colleagues to join you in suggesting hypotheses that might explain the symptoms.

Let the ideas flow, and write them all down. This is where having a diverse set of perspectives in the room really pays off. Your co-investigators will think of hypotheses that would never have occurred to you, and vice versa. The more of these you come up with, the more likely the actual explanation will be on the list.

A hypothesis can’t be just anything, though. A hypothesis must

- explain (at least some of) the symptoms,

- accord with all known facts, and

- be falsifiable (that is: if it were false, we’d be able somehow to prove it false).

For example, given the symptoms above, “requests to the storage API are getting queued up behind a long-running query” would not be a sound hypothesis, since it’s inconsistent with Symptom 3. If requests were queued up, we’d expect them to take longer before failing.

After some discussion, your hypothesis list might look like this:

Hypotheses

- A particular request causes an out-of-memory (OOM) event on a storage server, and all in-flight requests to that server get killed.

- A network hiccup causes connections between the load balancer and a storage server to be severed.

Requests to the storage API are getting queued up behind a long-running queryDiscarded because inconsistent with Symptom 3

- A network hiccup causes connections between storage API servers and a persistence layer node to be severed.

Again, use a numbered list. If a hypothesis is ruled out or deemed irrelevant, don’t delete it: you don’t want the list numbering to change. Instead, mark it in some with formatting. I use strikethrough. Gray works too.

Step 3: Select actions

Add an Actions header.

In a new numbered list, choose one or two actions that will advance the troubleshooting effort. Usually, you should pick actions that will rule out, or “falsify,” one or more of the hypotheses on the table.

To rule out Hypothesis 2 above, for instance, you could review the logs for one of the error spikes and check whether all the affected requests were associated with the same load balancer or the same storage server. If the requests are distributed across your infrastructure, then Hypothesis 2 is ruled out (and Hypothesis 1 as well, for that matter!).

When you agree upon actions, it’s best to assign them to individuals. Sometimes an action can be taken right away, and other times it’ll take a while and the group will have to reconvene later. But ownership should never be unclear.

Ruling out hypotheses the only purpose of actions in clinical troubleshooting. You can also assign actions that expand the group’s understanding of the problem, in order to generate new symptoms and new hypotheses. These actions can be things like, “Read the documentation on system X‘s network configuration,” or “Search for blog posts about error message E.” As long as there’s at least one hypothesis in the running, though, there ought to be at least one action in flight that could falsify it. That’s one of the ways clinical troubleshooting ensures constant progress.

Steps 4 through N: Cycle back through

When actions are completed, you get more information for the symptom list. More symptoms suggest new hypotheses. New hypotheses imply further actions. Just keep going through the cycle until you’re satisfied.

Sometimes you won’t be satisfied until you have a definitive diagnosis: a solid explanation for all the symptoms that’s been proven right. Other times, you’ll be satisfied as soon as you take an action that makes the problem go away, even if there’s still uncertainty about what exactly was going on.

In any case, clinical troubleshooting will reliably get you to the solution.

Keep things moving forward

In the absence of structure, collaborative diagnosis can stall out. Or worse, go backward.

With clinical troubleshooting, there’s always a next step forward. Teams that practice this method will consistently get to the bottom of technical mysteries, even when strapped for data or under intense pressure. And over time, as this scientific way of thinking becomes a habit, and then a culture, we come to understand the behavior of our system that much better.

I can teach your team how to do this. Get in touch.

3 questions that will make you a phenomenal rubber duck

As a Postgres reliability consultant and SRE, I’ve spent many hours being a rubber duck. Now I outperform even the incisive bath toy.

“Rubber duck debugging” is a widespread, tongue-in-cheek term for the practice of explaining, out-loud, a difficult problem that you’re stumped on. Often, just by putting our troubles into words, we suddenly discover insights that unlock progress. The person we’re speaking to could just as well be an inanimate object, like a rubber duck. Hence the term.

Rubber ducks are great, but a human can add even more value. In this article, I’ll share my 3 favorite questions to ask when someone comes to me feeling stumped in a troubleshooting endeavor. These questions work even when you have no particular expertise in the problem domain. Master them, and you’ll quickly start gaining a reputation as the person to talk to when you’re stuck. This is a great reputation to have!

Question 1: How did you first start investigating this?

As we investigate a problem, our focus shifts from one thing to another to another. We go down one path and forget about others. We zoom in on details and neglect to zoom back out. It’s easy to lose perspective.

“How did you first start investigating this?” works well because, through the act of recounting their journey from initial observation to where they are now, your colleague will often regain perspective they’ve lost along the way. And by asking this particular question, you avoid having to suggest that they may have lost perspective – which could make them defensive.

Even if your colleague hasn’t lost perspective, hearing the story of the investigation so far will help you ask better questions and help them organize their thoughts.

Question 2: What observations have you made?

In troubleshooting a complex problem, it’s easy to forget what you already know. As you go along, you make lots of observations, small and large, interesting and boring, relevant and irrelevant. You can’t hold them all in your head.

When someone’s stuck, it often helps to review their observations. Not theories, not difficulties, not actions: directly observed facts.

Reviewing observations can help in a few different ways:

- They may be entertaining a hypothesis that clashes with some previously learned (but since forgotten) fact. If so, they can now go ahead and discard that hypothesis.

- Juxtaposing two observations may suggest a hypothesis that never occurred to them before, because they never held those two observations in their head simultaneously.

- Listing out their observations may bring to mind something they haven’t looked at yet.

As your colleague recounts their observations, write them down in a numbered list. And, if you can, ask clarifying questions. Questions like “Does X always happen concurrently with Y, or only sometimes?” and “How does this differ from the normal behavior?”

Never underestimate the power of precisely stating the facts.

Question 3: If your hypothesis were wrong, how could we disprove it?

This question is my favorite.

One of the most common ways people get stuck in troubleshooting is tunnel vision. They get a single idea in their head about the cause of the problem, and that becomes all they can think about.

This question, “If your hypothesis were wrong, how could we disprove it?” flips the script. Instead of racking their brain trying to prove their theory, it gets them thinking about other possibilities. Asking this question can lead to lots of different outcomes, all of which represent progress:

- You come up with a way to disprove the hypothesis, and successfully disprove it. This may make your colleague sad for a few hours, but when they come back to the problem, they’ll make huge strides.

- You come up with a way to disprove the hypothesis, but fail to disprove it. The hypothesis is thus bolstered, and the next step becomes clear: elaborate a few different versions of it and try to disprove those.

- You can’t think of any way to disprove it. This means it’s probably not a hypothesis at all, since it’s not falsifiable. Therefore you must replace it with a new hypothesis. This may feel like a setback, but it’s really the only way forward.

How it fits together

Under the hood, these 3 questions are just different ways of invoking hypothetico-deductive reasoning, which I’ve written about previously (see Troubleshooting On A Distributed Team Without Losing Common Ground and You Know Who’s Smart? Friggin’ Doctors, Man.). I don’t know of any better way to achieve consistent problem-solving results in the face of complexity.

If you’re interested in learning how to apply these techniques in your career or in your organization, I can help. Shoot me an email!

Huh! as a signal

Every time our system fails, and we go to analyze the failure, we find ourselves saying things like “We didn’t know X was happening,” “we didn’t know Y could happen,” and so on. And it’s true: we didn’t know those things.

We can never predict with certainty what the next system failure will be. But we can predict, because painful experience has taught us, that some or all of the causes of that failure will be surprising.

We can use that!

When we go looking at data (and by “data” I mostly mean logs, traces, metrics, and so on, but data can be many things), sometimes we see something weird, and we go like, Huh!. That Huh! is a signal. If we follow that Huh! – get to the bottom of it, figure it out, make it not surprising anymore – two things happen. First, we get a chance to correct a latent problem which might some day contribute to a failure. And second, we make our mental model that much better.

Of course, any individual Huh! could turn out to be nothing. Perhaps there’s a bug. Perhaps circumstances have shifted, and our expectations no longer line up with reality. Or perhaps it’s just a monitoring blip. We won’t know until we run it down.

But, whatever the shortcomings of any particular investigation, a habit of investigating surprises has many attractive qualities. The main one is that we get to fix problems before those problems get worse, start bouncing off other problems, and cause fires. In other words: our system runs smoother. Consider what that’s worth.

Descriptive engineering: not just for post-mortems

In an organization that delivers a software service, almost all R&D time goes toward building stuff. We figure out what the customer needs, we decide how to represent their need as software, and we proceed to build that software. After we repeat this cycle enough times, we find that we’ve accidentally ended up with a complex system.

Inevitably, by virtue of its complexity, the system exhibits behaviors that we didn’t design. These behaviors are surprises, or – often – problems. Slowdowns, race conditions, crashes, and so on. Things that we, as the designers, didn’t anticipate, either because we failed to consider the full range of potential interactions between system components, or because the system was exposed to novel and unpredictable inputs (i.e. traffic patterns). Surprises emerge continuously, and most couldn’t have been predicted a priori from knowledge of the system’s design.

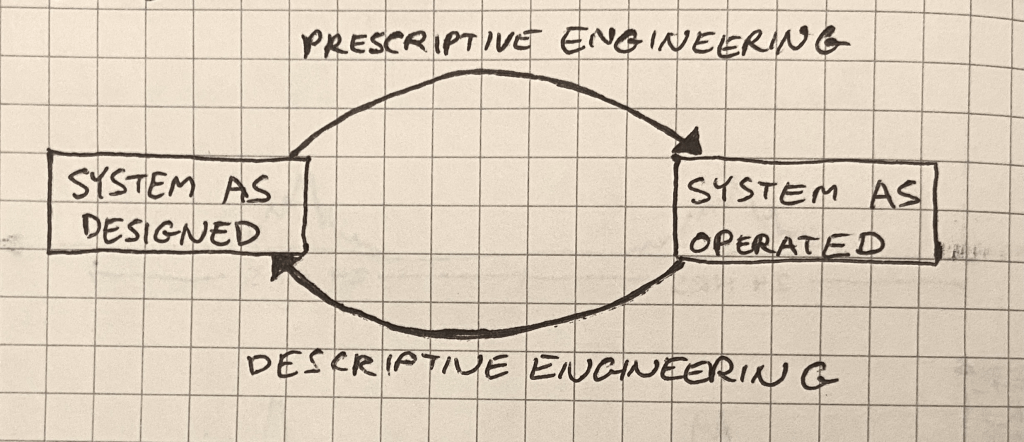

R&D teams, therefore, must practice 2 distinct flavors of engineering. Prescriptive engineering is when you say, “What are we going to build, and how?”, and then you execute your plan. Teams with strong prescriptive engineering capabilities can deliver high-quality features fast. And that is, of course, indispensable.

But prescriptive engineering is not enough. As surprises emerge, we need to spot them, understand them, and explain them. We need to practice descriptive engineering.

Descriptive engineering is usually an afterthought

Most engineers rarely engage with production surprises.

We’re called upon to exercise descriptive engineering only in the wake of a catastrophe or a near-catastrophe. Catastrophic events bring attention to the ways in which our expectations about the system’s behavior have fallen short. We’re asked to figure out what went wrong and make sure it doesn’t happen again. And, when that’s done, to put the issue behind us so we can get back to the real work.

In fact, descriptive engineering outside the context of a catastrophe is unheard of most places. Management tends to see all descriptive engineering as rework: a waste of time that could have been avoided had we just designed our system with more forethought in the first place.

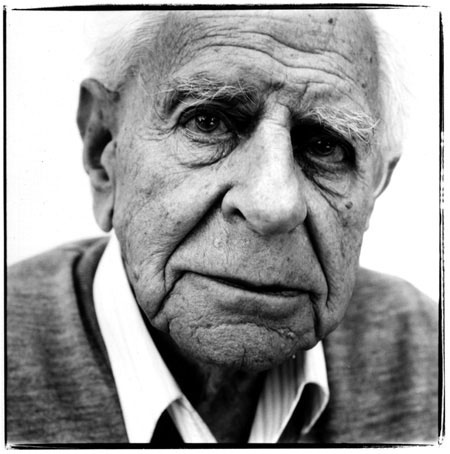

On the contrary. To quote the late, lamented Dr. Richard Cook:

The complexity of these systems makes it impossible for them to run without multiple flaws being present. Because these [flaws] are individually insufficient to cause failure they are regarded as minor factors during operations. … The failures change constantly because of changing technology, work organization, and efforts to eradicate failures.

How Complex Systems Fail, #4

A complex system’s problems are constantly shifting, recombining, and popping into and out of existence. Therefore, descriptive engineering – far from rework – is a fundamental necessity. Over time, the behavior of the system diverges more and more from our expectations. Descriptive engineering is how we bring our expectations back in line with reality.

In other words: our understanding of a complex system is subject to constant entropic decay, and descriptive engineering closes an anti-entropy feedback loop.

Where descriptive engineering lives

Descriptive engineering is the anti-entropy that keeps our shared mental model of the system from diverging too far from reality. As such, no organization would get very far without exercising some form of it.

But, since descriptive engineering effort is so often perceived as waste, it rarely develops a nucleus. Instead, it arises in a panic, proceeds in a hurry, and gets abandoned half-done. It comes in many forms, including:

- handling support tickets

- incident response

- debugging a broken deploy

- performance analysis

In sum: the contexts in which we do descriptive engineering tend to be those in which something is broken and needs to be fixed. The understanding is subservient to the fix, and once the fix is deployed, there’s no longer a need for descriptive engineering.

Moreover, since descriptive engineering usually calls for knowledge of the moment-to-moment interactions between subsystems in production, and between the overall system and the outside world, this work has a habit of being siphoned away from developers toward operators. This siphoning effect is self-reinforcing: the team that most often practices descriptive engineering will become the team with the most skill at it, so they’ll get assigned more of it.

This is a shame. By adopting the attitude that descriptive engineering need only occur in response to catastrophe, we deny ourselves opportunities to address surprises before they blow up. We’re stuck waiting for random, high-profile failures to shock us into action.

What else can we do?

Instead of doing descriptive engineering only in response to failures, we must make it an everyday practice. To quote Dr. Cook again,

Overt catastrophic failure occurs when small, apparently innocuous failures join to create opportunity for a systemic accident. Each of these small failures is necessary to cause catastrophe but only the combination is sufficient to permit failure. Put another way, there are many more failure opportunities than overt system accidents.

How Complex Systems Fail, #3

We won’t ever know in advance which of the many small failures latent in the system will align to create an accident. But if we cultivate an active and constant descriptive engineering practice, we can try to make smart bets and fix small problems before they align to cause big problems.

What would a proactive descriptive engineering practice look like, concretely? One can imagine it in many forms:

- A dedicated team of SREs.

- A permanent cross-functional team composed of engineers familiar with many different parts of the stack.

- A cultural expectation that all engineers spend some amount of their time on descriptive engineering and share their results.

- A permanent core team of SREs, joined by a rotating crew of other engineers. Incidentally, this describes the experimental team I’m currently leading IRL, which is called Production Engineering.

I have a strong preference for models that distribute descriptive engineering responsibility across many teams. If the raison d’être of descriptive engineering is to maintain parity between our expectations of system behavior and reality, then it makes sense to spread that activity as broadly as possible among the people whose expectations get encoded into the product.

In any case, however we organize the effort, the main activities of descriptive engineering will look much the same. We delve into the data to find surprises. We pick some of these surprises to investigate. We feed the result of our investigations back into development pipeline. And we do this over and over.

It may not always be glamorous, but it sure beats the never-ending breakdown.

Falsifiability: why you rule things out, not in

This June, I had the honor of speaking at O’Reilly Velocity 2016 in Santa Clara. My topic was Troubleshooting Without Losing Common Ground, which I’ve written about and written about before that too.

I was pretty happy with my talk, especially the Star Trek: The Next Generation vignette in the middle. It was a lot of ideas to pack into a single talk, but I think a lot of people got the point. However, I did give a really unsatisfactory answer (30m46s) to the first question I received. The question was:

In the differential diagnosis steps, you listed performing tests to falsify assumptions. Are you borrowing that from medicine? In tech are we only trying to falsify assumptions, or are we sometimes trying to validate them?

I didn’t have a real answer at the time, so I spouted some bullshit and moved on. But it’s a good question, and I’ve thought more about it, and I’ve come up with two (related) answers: a common-sense answer and a pretentious philosophical answer.

The Common Sense Answer

My favorite thing about differential diagnosis is that it keeps the problem-solving effort moving. There’s always something to do. If you’re out of hypotheses, you come up with new ones. If you finish a test, you update the symptoms list. It may not always be easy to make progress, but you always have a direction to go, and everybody stays on the same page.

But when you seek to confirm your hypotheses, rather than to falsify others, it’s easy to fall victim to tunnel vision. That’s when you fixate on a single idea about what could be wrong with the system. That single idea is all you can see, as if you’re looking at it through a tunnel whose walls block everything else from view.

Tunnel vision takes that benefit of differential diagnosis – the constant presence of a path forward – and negates it. You keep running tests to try to confirm your hypothesis, but you may never prove it. You may just keep getting tests results that are consistent with what you believe, but that are also consistent with an infinite number of hypotheses you haven’t thought of.

A focus on falsification instead of verification can be seen as a guard against tunnel vision. You can’t get stuck on a single hypothesis if you’re constrained to falsify other ones. The more alternate hypotheses you manage to falsify, the more confident you get that you should be treating for the hypotheses that might still be right.

Now, of course, there are times when it’s possible to verify your hunch. If you have a highly specific test for a problem, then by all means try it. But in general it’s helpful to focus on knocking down hypotheses rather than propping them up.

The Pretentious Philosophical Answer

I just finished Karl Popper’s ridiculously influential book The Logic of Scientific Discovery. If you can stomach a dense philosophical tract, I would highly recommend it.

Published in 1959 – but based on Popper’s earlier book Logik der Forschung from 1934 – The Logic Of Scientific Discovery makes a then-controversial [now widely accepted (but not universally accepted, because philosophers make cats look like sheep, herdability-wise)] claim. I’ll paraphrase the claim like so:

Science does not produce knowledge by generalizing from individual experiences to theories. Rather, science is founded on the establishment of theories that prohibit classes of events, such that the reproducible occurrence of such events may falsify the theory.

Popper was primarily arguing against a school of thought called logical positivism, whose subscribers assert that a statement is meaningful if and only if it is empirically testable. But what matters to our understanding of differential diagnosis isn’t so much Popper’s absolutely brutal takedown of logical positivism (and damn is it brutal), as it is his arguments in favor of falsifiability as the central criterion of science.

I find one particular argument enlightening on the topic of falsification in differential diagnosis. It hinges on the concept of self-contradictory statements.

There’s an important logical precept named – a little hyperbolically – the Principle of Explosion. It asserts that any statement that contradicts itself (for example, “my eyes are brown and my eyes are not brown”) implies all possible statements. In other words: if you assume that a statement and its negation are both true, then you can deduce any other statement you like. Here’s how:

- Assume that the following two statements are true:

- “All cats are assholes”

- “There exists at least one cat that is not an asshole”

- Therefore the statement “Either all cats are assholes, or 9/11 was an inside job” (we’ll call this Statement A) is true, since the part about the asshole cats is true.

- However, if the statement “there exists at least one cat that is not an asshole” is true too (which we’ve assumed it is) and 9/11 were not an inside job, then Statement A would be false, since neither of its two parts would be true.

- So the only way left for Statement A to be true is for “9/11 was an inside job” to be a true statement. Therefore, 9/11 was an inside job.

- Wake up, sheeple.

The Principle of Explosion is the crux of one of Popper’s most convincing arguments against the Principle of Induction as the basis for scientific knowledge.

It was assumed by many philosophers of science before Popper that science relied on some undefined Principle of Induction which allowed one to generalize from a finite list of experiences to a general rule about the universe. For example, the Principle of Induction would allow one to deduce from enough statements like “I dropped a ball and it fell” and “My friend dropped a wrench and it fell” to “When things are dropped, they fall.” But Popper argued against the existence of the Principle of Induction. In particular, he pointed out that:

If there were some way to prove a general rule by demonstrating the truth of a finite number of examples of its consequences, then we would be able to deduce anything from such a set of true statements.

Right? By the Principle of Explosion, a self-contradictory statement implies the truth of all statements. If we accepted the Principle of Induction, then the same evidence that proves “When things are dropped, they fall” would also prove “All cats are assholes and there exists at least one cat that is not an asshole,” which would prove every statement we can imagine.

So what does this have to do with falsification in differential diagnosis? Well, imagine you’ve come up with these hypotheses to explain some API slowness you’re troubleshooting:

Hypothesis Alpha: contention on the table cache is too high, so extra latency is introduced for each new table opened

Hypothesis Bravo: we’re hitting our IOPS limit on the EBS volume attached to the database server

There are many test results that would be compatible with Hypothesis Alpha. But unless you craft your tests very carefully, those same results will also be compatible with Hypothesis Bravo. Without a highly specific test for table cache contention, you can’t prove Hypothesis Alpha through a series of observations that agree with it.

What you can do, however, is try to quickly falsify Hypothesis Bravo by checking some graphs against some AWS configuration data. And if you do that, then Hypothesis Alpha is the your best remaining guess. Now you can start treating for table cache contention on the one hand, and attempting the more time-consuming process (especially if it’s correct!) of falsifying Hypothesis Alpha.

Isn’t this kind of abstract?

Haha OMG yes. It’s the most abstract. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a useful idea.

If it’s your job to troubleshoot problems, you know that tunnel vision is very real. If you focus on generating alternate hypotheses and falsifying them, you can resist tunnel vision’s allure.