About a year into COVID, when we were all at least 40% insane – and I had recently become a dad, so I was at like 65/70% – I became unaccountably obsessed with a pointless and, for almost all of history, unanswerable question:

What’s the farthest any person has been from the nearest other person?

Having not much better to do while my infant napped, I embarked on a long, spreadsheet-fueled journey of the mind to try to answer this question. I wanted to answer it not just for the present day (which, as we’ll see, is relatively easy), but for every point in human history.

Some of what follows is grim, I have to warn you. For most of human existence, if you were significantly far from all other people, you were probably about to die. But nevertheless, you’d have a chance of breaking humanity’s Loneliness Record before your impending death!

Early humanity

Back when there were only 2 humans in the world, every time they got farther from each other, both of them would simultaneously break the Loneliness Record.

However, unless you’re a Biblical literalist, it’s hard to imagine that there was ever a time when only 2 humans existed. Surely Homo sapiens emerged over the course of generations, each composed of beings that, in different ways, more or less resembled modern humans. So it makes more sense to start with the first migrations out of Africa, between 70,000 and 100,000 years ago. That’s when the distances start to get interesting.

Prehistory

As our ancestors migrated out of central Africa, they pushed into wilderness that was uninhabited by other humans. So we might think that they would have had plentiful opportunities to break the Loneliness Record.

However, we tend to travel in groups, especially when we’re going far. And you can’t break the Loneliness Record if you’re traveling in a group. Unless things go terribly wrong.

For my money, the most likely way for the Loneliness Record to have been broken during this period would be:

- A group of travelers sets out.

- They happen to go in a direction away from the rest of humanity.

- They travel far – farther than anyone would be able to travel alone.

- But then – uh oh! There’s a rockslide or something, and they all die.

In this scenario, the last of the travelers to die breaks our Record. Hooray!

Another way it could have happened is if someone got swept out to sea on a log. Since sailing ships hadn’t been invented yet, there’d be no other humans out there.

Now, you might wonder, what about camels? Once humans domesticated the camel, couldn’t they travel much farther over land? Yes! But humans didn’t figure out how to ride camels until about 3000 BC, by which point Austronesian peoples had already, for 15,000 years, been…

Sailing

Sailing ups the ante, because nobody lives in the ocean, and you can get a lot farther sailing a boat than clinging to a log. One of the same issues still confronts us, though: long distance sailing is usually done by groups, not individuals.

It seems likely that early sailors would have broken the loneliness record from time to time. Say your ship gets caught in a storm and blown 100 km off course. Then it sinks. If you’re the last survivor, you might get the dubious honor of breaking humanity’s Loneliness Record. Certainly, you could get a lot farther from other humans by sailing than by walking on land.

Once sailing started being used for trade, though, one has to imagine that the Record stopped getting broken so much. Advancements in sailing technology would bring distance gains, but they would also bring congestion. If sailing ships are frequently crossing the sea between nations, then even if you’re lucky (?) enough to be the doomed last survivor of a remote shipwreck, there’s probably another ship just over the horizon. So no Loneliness Trophy for you.

Of course, we can’t know when the Loneliness Record was broken during this period or by whom, because there’s no documentation. So let’s talk about the first era in which I was able to find any solid documentation of a person being Record-breakingly isolated.

The age of Antarctic Exploration

For some reason, people in the early 1900s thought it would be a really fun idea to trek to the South Pole. For Robert Falcon Scott, a Royal Navy officer and one of the first to make the trip, it was… not.

Scott led the Terra Nova expedition, an attempt to reach the South Pole for the first time in human history. But on January 17, 1912, when Scott’s party got to the Pole, they were devastated to find they’d been bested by the expedition of Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. Amundsen had reached the South Pole just 34 days before Scott.

If the explorers thought losing the race was bad, they were in for much worse. After a series of disasters, the entire party perished. Which is a bummer. But, on the bright side, they were 160 km from the rest of humanity when they finally succumbed to the cold. This is the first occurrence I could find of a plausible Loneliness Record-setting event with a specific distance and set of names. So congratulations to the Terra Nova expedition!

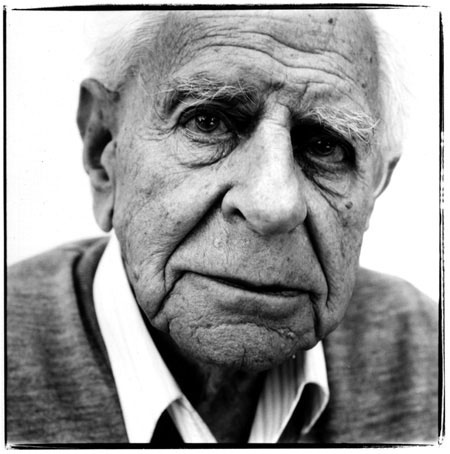

But even so, their record didn’t last long, on the historical scale. In 1934, Richard E. Byrd, an American Naval officer who had in 1926 made the first flight over the South Pole (but that’s not of interest here, since he had a co-pilot) operated a small weather station in Antarctica. The station was called Bolling Advance Base, and it was situated 196 km from the nearest inhabited location: Little America II base, on the coast.

Eventually, around August of 1934, Byrd stopped sending intelligible radio transmissions back to Little America II. A rescue party was dispatched, which found Byrd near death, suffering from frostbite and carbon monoxide poisoning. He survived to lead several more Antarctic expeditions, and for the rest of his life, he held the record (at least as far as I can tell) for Loneliest Person!

And, by the same token, Byrd had become the last person to break the Loneliness Record while staying on Earth.

The final frontier

Spacefaring really changed the scale of the Loneliness Record problem. Now our species was no longer confined to a 2-dimensional surface.

The first (human) spacefarer was Comrade Yuri Gagarin of the USSR. He took off from Baikonur Cosmodrome on April 12, 1961, and traveled in a parabolic orbit that took him 327 km above the surface of the Earth. That’s 131 km farther than Byrd’s weather station. Congratulations, Yuri Gagarin!

Gagarin got to hold this record for several years. His space mission, Vostok 1, had a higher apogee than any other of the 1-crewmember space missions (the USSR’s Vostok program and the USA’s Mercury program). And after those, we stopped sending people into space alone.

327 km is pretty far. And since the apogee of Vostok 1’s parabola was over the south Pacific, Gagarin’s distance from other humans might even have been somewhat greater. So it was eight years before the Loneliness Record was broken again. This time, though, it was utterly smashed, by an order of magnitude.

A little while after Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong descended to the lunar surface on July 24, 1969, Michael Collins (who continued orbiting the moon) reached a distance of 3592 km (the Moon’s diameter and change) from his fellow travelers.

The remaining Apollo missions

Now from here, for Apollos 12–17, things are a little fuzzier. A lot depends on the exact trajectories of the capsules, and I won’t go into it here (but corner me with a pen and a cocktail napkin some time). So I might have made a mistake here, even beyond the obvious mistake of embarking on this pointless thought experiment in the first place. But, after reviewing the numbers, I think the next Record-breaking event occurred on Apollo 15:

And the last time the Loneliness Record was broken was on the Apollo 16 mission, by Command Module pilot Ken Mattingly:

My heartfelt congratulations to Ken Mattingly, the World Champion of Loneliness!

History isn’t over… yet!

One day – assuming humanity doesn’t somehow burn itself out of existence first 😉 – somebody is gonna come for what’s Ken’s.

In Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars, Arkady Bogdanov and Nadia Cherneshevsky are among the First Hundred humans to live on Mars. They regularly travel the planet’s empty surface in lighter-than-air craft. Something like that could get you a Loneliness Record.

More likely, the next Record breaker will be the last survivor of some space voyage. On Mars, you can’t get meaningfully more than 6,800 km from any other point. But if you’re on the way to Mars and life support fails, then someone gets to break Mattingly’s record by probably several orders of magnitude.

This article is off the beaten path for my blog, which is usually about incident response and site reliability engineering. I hope you’ve enjoyed this pointless endeavor as much as I enjoyed wasting my time putting it together!