Ask an engineering leader about their incident response protocol and they’ll tell you about their severity scale. “The first thing we do is we assign a severity to the incident,” they’ll say, “so the right people will get notified.”

And this is sensible. In order to figure out whom to get involved, decision makers need to know how bad the problem is. If the problem is trivial, a small response will do, and most people can get on with their day. If it’s severe, it’s all hands on deck.

Severity correlates (or at least, it’s easy to imagine it correlating) to financial impact. This makes a SEV scale appealing to management: it takes production incidents, which are so complex as to defy tidy categorization on any dimension, and helps make them legible.

A typical SEV scale looks like this:

- SEV-3: Impact limited to internal systems.

- SEV-2: Non-customer-facing problem in production.

- SEV-1: Service degradation with limited impact in production.

- SEV-0: Widespread production outage. All hands on deck!

But when you’re organizing an incident response, is severity really what matters?

The Finger of God

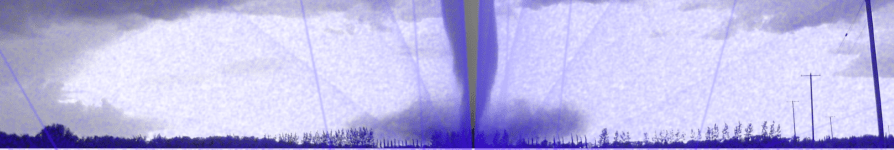

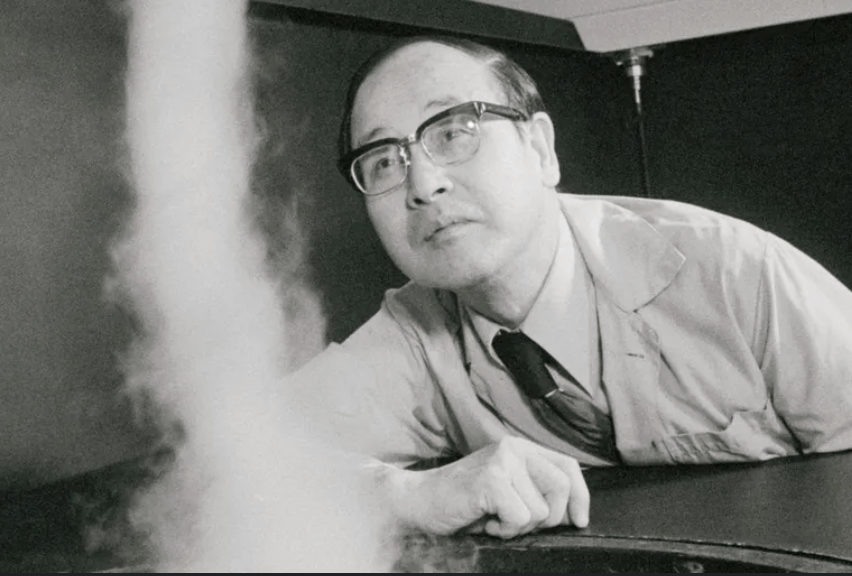

SEV scales are rather like the Fujita Scale, which you may recall from the American film masterpiece Twister (1996). The Fujita Scale was invented in 1971 by Ted Fujita (seen here with Whoosh, a miniature tornado he rescued from tornado poachers and raised as his own).

The Fujita scale classifies tornados according to the amount of damage they cause to human-built structures and vegetation:

| F0 | Light damage | Broken windows; minor roof damage; tree branches broken off. |

| F1 | Moderate damage | Cars pushed off road; major roof damage; significant damage to mobile homes |

| F2 | Significant damage | Roof loss; collapse of exterior walls; vehicles lifted off ground; large numbers of trees uprooted |

| F3 | Severe damage | A few parts of buildings left standing; train cars overturned; total loss of vegetation |

| F4 | Devastating damage | Homes reduced to debris; trains lifted off ground and turned into projectiles |

| F5 | Incredible damage | Well-anchored homes lifted into the air and obliterated; steel-reinforced structures leveled; “Incredible phenomena can and will occur” |

Or, more colorfully,

BILL: It’s the Fujita scale. It measures a tornado’s intensity by how much it eats.

MELISSA: Eats?

BILL: Destroys.

LAURENCE: That one we encountered back there was a strong F2, possibly an F3.

BELTZER: Maybe we’ll see some 4’s.

HAYNES: That would be sweet!

BILL: 4 is good. 4 will relocate your house very efficiently.

MELISSA: Is there an F5?

(Silence.)

MELISSA: What would that be like?

JASON: The Finger of God.

Fujita scores are not assigned at the moment a tornado is born, nor at the moment it is observed, nor yet the moment it’s reported to the National Weather Service. They’re assigned only after the damage has been assessed. During this assessment, many tools may be brought to bear, including weather radar data, media reports, witness testimony, and expert elicitation. It can take quite a while. It may even be inconclusive: the Enhanced Fujita scale has a special “unknown” score for tornados, which is used for storms that happen to cross an area devoid of buildings or vegetation to “eat.” No matter how immensely powerful a tornado may be, if it causes no surveyable damage, its score is unknown.

Is severity even the point?

In many cases, when we’re just beginning to respond to a software incident, we don’t yet know how bad a problem we’re dealing with. We can try to use the evidence at hand to hazard a guess, but the evidence at hand is likely to be scant, ambiguous, and divorced from context. (I’m by no means the first to notice these issues with SEV scales – see Fred Hebert’s Against Incident Severities and in Favor of Incident Types for an excellent take.)

Maybe all we have is a handful of support tickets. A handful of support tickets could imply a small hiccup, or it could point to the start of a major issue. We don’t know yet.

Or the evidence might be a single alert about a spike in error rate. Are the errors all for a single customer? What’s the user’s experience? What’s a normal error rate?

This uncertainty makes it quite hard to assign an accurate incident severity – at least, without doing additional, time-consuming research. Ultimately, though, what incident response calls for is not a judgement of severity. It’s a judgement of complexity.

The Incident Command System, employed by disaster response agencies such as FEMA and the DHS, provides an illustration of complexity-based scoring. It defines a range of incident types:

| Incident type | Complexity | Examples |

| Type 5 | Up to 6 personnel; no written action plan required | Vehicle fire; injured person; traffic stop |

| Type 4 | “Task Force” or “Strike team” required; multiple kinds of resources required | Hazmat spill on a roadway; large commercial fire |

| Type 3 | Command staff positions filled; incident typically extends into multiple shifts; may require an incident base | Tornado damage to small section of city; detonation of a large explosive device; water main break |

| Type 2 | Resources may need to remain on scene several weeks; multiple facilities required; complex aviation operations may be involved | Railroad car hazmat leak requiring multi-day evacuation; wildfire in a populated area; river flooding affecting an entire town |

| Type 1 | Numerous facilities and resource types required; coordination between federal assets and NGO responders; 1000 or more responders | Pandemic; Category 4 hurricane; large wind-driven wildfire threatening an entire city |

Complexity-based classification has a key advantage over that based on impact. Namely: by the time you’ve thought enough to know how complex a response you need, you already have the beginning of a plan. In other words, whereas the impact-based Fujita system is suited to analysis, the complexity-based ICS types are suited to action.

A complexity scale for software incidents

Impact-based systems, like SEV scores, do little to support responders at incident time. A complexity-based system is far better. Here’s an example of a complexity-based system for software incidents:

| Complexity | Example | |

| C-1 | A handful of engineers from a single team. No handoffs. | Disk space is filling up on a log server |

| C-2 | Coordination between teams and/or across shifts. Customer support may be involved. | Out-of-control database queries causing a performance degradation for some customers |

| C-3 | Coordination among 3 or more teams. Customer-facing status posts may be called for. Deploys may be paused. | Outage of account-administrative functions. Severe delay in outgoing notifications. |

| C-4 | Sustained, intense coordination cutting across all engineering team boundaries. Third-party relationships activated. Executives may be involved. | Website down due to unexplained network timeouts. Cloud provider region failure. |

If you’re in control of your company’s incident response policy, consider whether a severity scale is going to be helpful to responders in the moment. You might come to the conclusion that you don’t need any scale at all! But if you do need to classify ongoing incidents, would you rather use a system that asks “How bad is it?,” or one that asks “What’s our plan?”