When queues break down, they break down spectacularly. Buffer overruns! Out-of-memory crashes! Exponential latency spikes! It’s real ugly. And what’s worse, making the queue bigger never makes the problems go away. It always manages to fill up again.

If 4 of your last 5 incidents were caused by problems with a queue, then it’s natural to want to remove that queue from your architecture. But you can’t. Queues are not just architectural widgets that you can insert into your architecture wherever they’re needed. Queues are spontaneously occurring phenomena, just like a waterfall or a thunderstorm.

A queue will form whenever there are more entities trying to access a resource than the resource can satisfy concurrently. Queues take many different forms:

- People waiting in line to buy tickets to a play

- Airplanes sitting at their gates for permission to taxi to the runway

- The national waiting list for heart transplants

- Jira tickets in a development team’s backlog

- I/O operations waiting for write access to a hard disk

Though they are embodied in different ways, these are all queues. A queue is simply what emerges when more people want to use a thing than can simultaneously do so.

Let me illustrate this point by seeing what happens when we try to eliminate queueing from a simple web application.

The queueing shell game

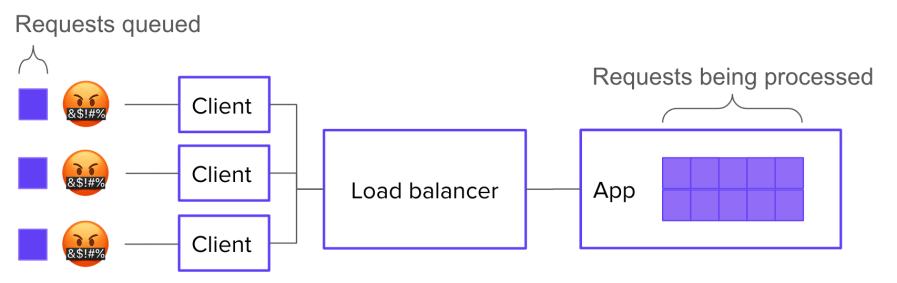

Let’s say your system has 10 servers behind a load balancer, and each server has enough resources to handle 10 concurrent requests. It follows that your overall system can handle 100 concurrent requests.

Now let’s say you have 170 requests in flight. 100 of those requests are actively being processed. What happens to the other 70?

Well, the most straightforward, job-interview-systems-design answer would be: they wait in a queue, which is implemented in the application logic.

This is great because it lets you show off your knowledge of how to implement a queue. But it’s not super realistic. Most of the time, we don’t make our applications worry about where the connections are coming from: the application just worries about serving the requests it gets. If your application simply accept()s new connections and starts working on them, then you don’t need to build a queue into it.

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a queue! Instead of forming inside the application, a queue will form in the SYN backlog of the underlying network stack:

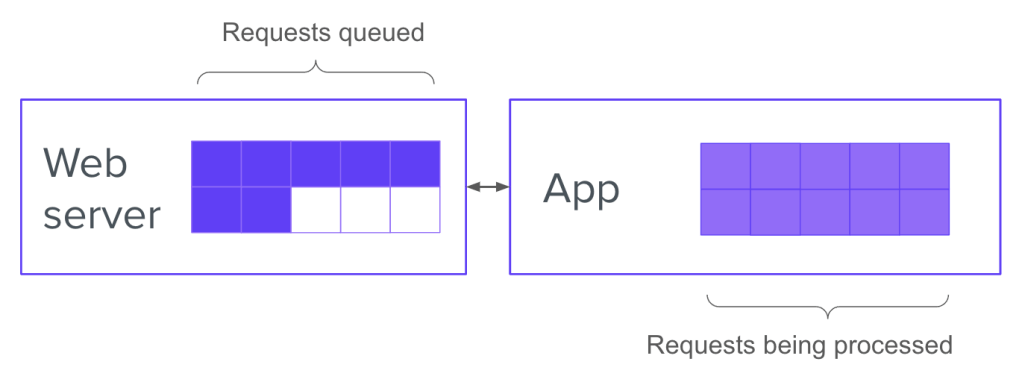

Of course, it can be advantageous instead to run your application through web server software that handles queueing for you. Then your 70 waiting requests will be queued up inside the web server:

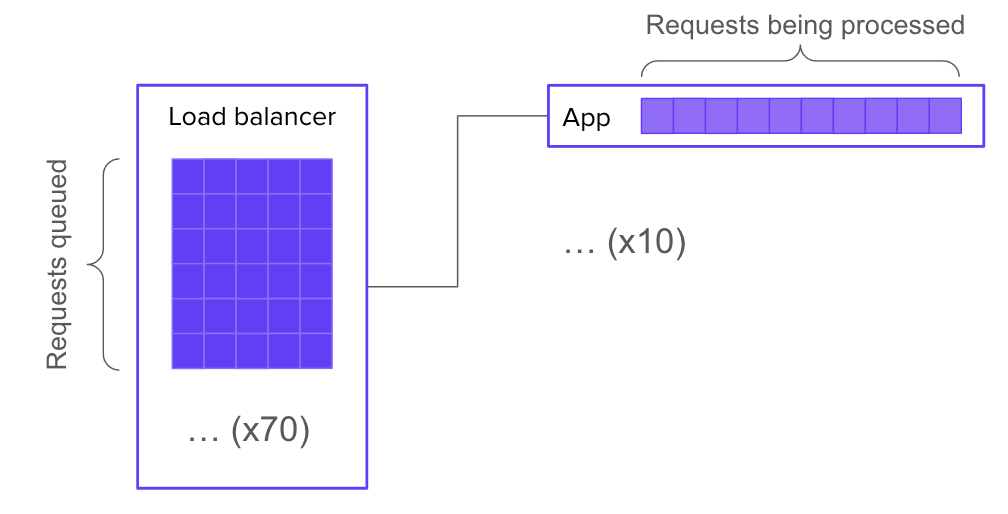

But what if your web server doesn’t have any queueing built in? Then is there no queue? Of course not. There must be a queue, because the conditions for queue formation are still met. The queue may again take the form of a SYN backlog (but this time on the web server’s socket instead of the application’s socket). Or, it might get bumped back out to the load balancer (in which case, you’ll need a much bigger queue).

If you really do not want a queue, then you can tell your load balancer not to queue requests, and instead to just send 503 errors whenever all backends are busy. Then there’s no queue.

OR IS THERE?? Because, presumably, the requests you’re getting are coming from clients out there on the Internet that want the resource. Many of those clients, unless they’re lazy, will re-request the resource. So in effect, you’ve only moved the queue again:

Now, if you control the client logic, you’re in luck. You can explicitly tell clients not to retry. Finally, you’ve eliminated the queue.

LOL, just kidding. Because the human, your customer, still wants the resource. So what will they do? They will keep trying until they either get their data or get bored. Again, by trying to eliminate the queue, you’ve just moved it – this time, into your customers’ minds.

Requests represent intentions

If you have more requests to answer than you have space for, you will have a queue. The only way to eliminate the queue would be to eliminate the extra requests. But a request doesn’t start the moment you get a connection to your load balancer – it starts the moment your customer decides to load a resource.