One piece of common-sense advice that you often hear about incident response is,

Fix it first. Ask “why” later.

This chestnut is often deployed to combat what is perceived as excessive investigation. And like most common-sense advice, it’s approximately right in lots of situations. But it misses a crucial point, and at its worst, this attitude perpetuates failure.

Diagnosing and fixing

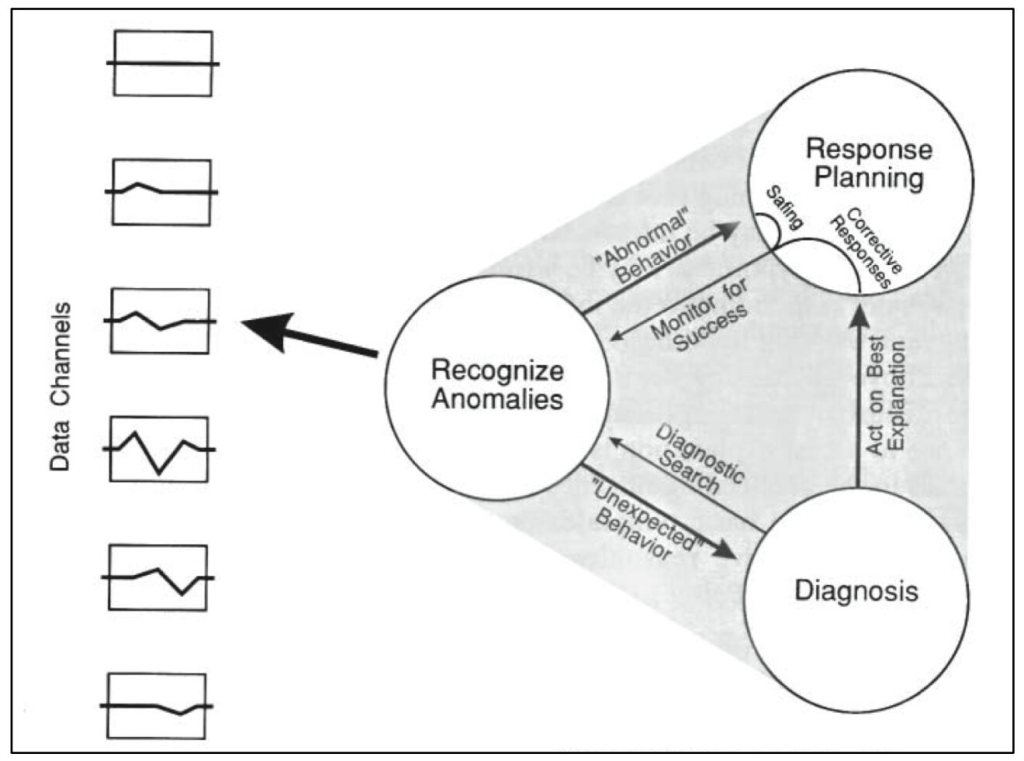

Incident response comprises two intertwined, but distinct, activities: diagnosing and fixing. This point is illustrated in David Woods’ 1995 paper, Cognitive demands and activities in dynamic fault management: abductive reasoning and disturbance management (which uses the term “response planning” for what I’m calling “fixing”):

Diagnosing and fixing can involve overlapping activities, such that they blend together during incident response. For example, if you have diagnosed a partial outage as resulting from a web server that’s used up all its allotted file handles, you might restart that web server. This would be a “diagnostic intervention,” in that it serves to advance both the fix (if your diagnosis holds water, then restarting the web server will fix the problem) and the diagnosis (if restarting the web server fixes the problem, then you have additional evidence for your diagnosis; if it doesn’t, then you know you need a new diagnosis).

The fact that fixing and diagnosing often converge to the same actions doesn’t change the fact that these two concurrent activities have different goals. The goal of fixing is to bring the system into line with your mental model of how it’s supposed to function. The goal of diagnosing is to bring your mental model into line with the way the system is actually behaving.

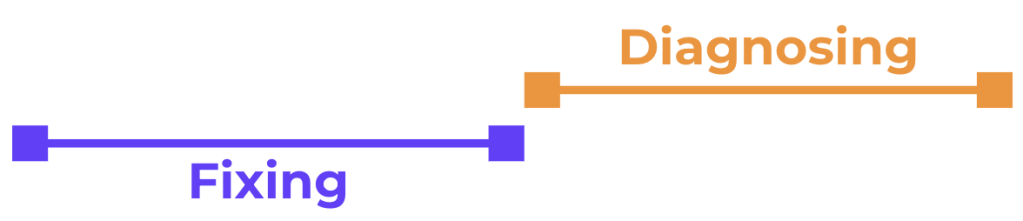

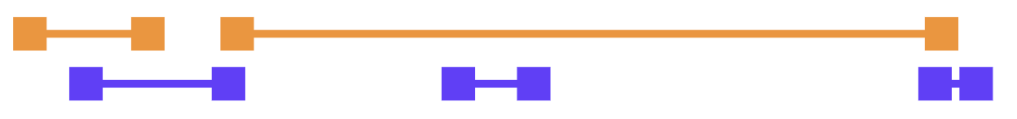

Usually these two goals are aligned with one another, but sometimes they demand different actions. And that’s what opens the door for someone to say, “Let’s fix the problem first and ask questions later.” However, this implies a naïve conception of the incident response process, which I’ll represent schematically here:

In this view, you fix first, then you diagnose – perhaps in a post-mortem or a root-cause analysis. But in a field like ours, in which complex systems are at play, this is simply not how things work. A complex system has infinitely many possible failure modes. Therefore there are infinitely many possible actions that might be necessary to recover from a failure. In order to even attempt a fix, you must always start with some kind of diagnosis.

Sure, sometimes the diagnostic effort might be very brief and straightforward. Suppose you get an alert about some new error happening in production. You immediately recognize the error as resulting from a code change you just deployed, and you revert the change.

Because the diagnosis was so quick, it may feel like you simply fixed the problem as soon as you saw it. But you still undertook a diagnostic process. You saw the alert and developed a hypothesis (“My code change caused these errors”), and that hypothesis turned out to be right. Had you truly done no diagnosis, then you wouldn’t have known what to do. The incident actually looked like this:

Contrast this with another scenario. You get alerted about slow page-loads. Together with a team, you begin to investigate the slowness. But no explanation is forthcoming. It takes an hour of searching logs, reading documentation, and consulting with other teams before you have a satisfactory explanation: an mission-critical cache object has gotten too large to store in the cache, so it has to be fetched from origin on every request. Upon reaching this diagnosis, you immediately know what to do to fix the problem:

During this long diagnostic phase, nobody would have said, “Fix the problem first. Worry about ‘why’ later.” The diagnostic effort was clearly pursued in service of fixing the issue. Whether it takes a split-second or a week, a diagnosis (at least a differential diagnosis) always has to be reached before the problem can be fixed.

These are simple examples. In a more general case, you do some diagnosis, which produces a potential fix. That fix doesn’t work (or only partly works), so diagnosis continues until another potential fix presents itself. And since multiple responders are present on the call, diagnosis doesn’t generally have to totally halt in order for fixes to be pursued:

The “Fix first” shibboleth comes out when someone perceives that there is already a potential fix, but nobody is applying that fix yet. So when you hear it, or you’re tempted to speak it yourself, first ask yourself:

- Is there a potential fix on the table?

- Is that potential fix worth pursuing immediately?

If the answer to both of these questions is “yes,” then by all means, get on the fix. But don’t halt diagnosis to do so, unless you’re so labor-constrained that you must.

If either question elicits a “no,” then you should talk through your reasoning with the group and make the case for pursuing further diagnosis before taking action.

Fix first, ask questions later.

Ask questions until you can fix.

––

I teach Scientific Incident Response in 4 Days, an in-depth incident response training course for engineering teams.